An investigation on the intricacies of video game narration and storytelling.

Author’s Note: This is a paper I wrote last quarter for my computer games and society course. It is about video game narrative. Enjoy!

As consumers, we usually see video games as a source of entertainment and fun. Not only are they a way for us to take a break from reality, but they also allow us to express our creative freedom. That is one of the reasons why gaming has become such a mainstream phenomenon in recent years; playing video games is a simple and easy way to have a good time, whether you are alone or with friends and family. However, in the past several years, people have been using video games for far more than just merely entertainment. As our technology has progressed, so too has the level of detail in our video game worlds. The emergence of the indie game scene now allows almost anyone with a computer and a creative mind to create his or her own game. Thanks to such developments, we now have a broader range of games than ever before, many of which explore new territories that at one time were never thought to be possible in the realm of video games.

In the past two to three years, there has been a trend in video game design that focuses on storytelling over gameplay. These “narrative-focused” video games come in a variety of different genres, from classic point-and-click games to more open, three-dimensional adventures. Unlike most games, however, these video games do not engage players through their gameplay; rather, they try to establish an emotional connection between the game and the player through interactive storytelling. Below is an analysis on three separate video games that that attempt to establish such a connection in vastly different ways: Dear Esther by The Chinese Room, To the Moon by Freebird Games, and The Walking Dead by Telltale Games.

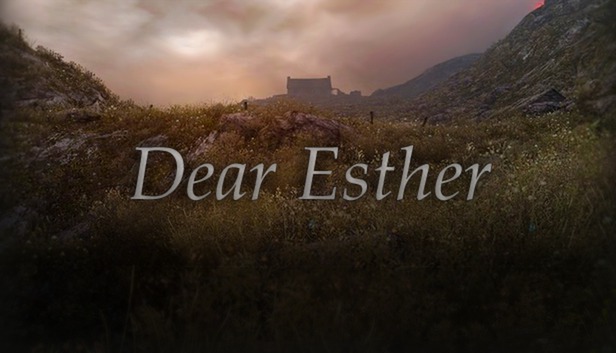

Dear Esther and the Narrative Experience

Dear Esther is an adventure game that originally began as a free downloadable mod for Valve’s Half Life 2. In 2012, the original creators of the mod The Chinese Room released a full high-definition standalone remake for Dear Esther on PC. Unlike most adventure games, Dear Esther is played from a first-person perspective and emphasizes exploration over combat and conflict. Upon its release, some critics applauded Dear Esther for seemingly breaking the boundaries of what defines a game while others criticized it for its lack of traditional game elements (Kuchera).

In the past two to three years, there has been a trend in video game design that focuses on storytelling over gameplay.

The game’s official website describes Dear Esther as “… a ghost story, told using first-person gaming technologies” (Briscoe). The game’s plot revolves around a mysterious woman by the name of Esther, who an unnamed male narrator repeatedly references as the player progresses through the game. What makes Dear Esther unique is that the game randomizes the way in which you experience the story; in some playthroughs the narrator may leave out some information pertaining to Esther, while in others he may narrate the story in a different order. This concept enforces the idea that games, unlike other media, can tell a story in a nonlinear fashion allowing the player to experience a game differently each time (Dickey 73).

Indeed, there are several other games that take a similar narrative approach as Dear Esther, but Dear Esther specifically focuses on the delivery of the narrative itself. The story is never truly revealed to the player; the purposefully cryptic nature of the narrator’s messages forces the player to think outside the grand scheme of the game. Furthermore, the complete lack of traditional gameplay elements as combat and conflict gives the player no other choice but to focus on unravelling the mystery behind Esther (Ostenson 76). Games researcher Jesper Juul summarizes this point well in his article pertaining to narratives in video games: “… the more open a narrative is to interpretation, the more emphasis will be on the reader/viewer’s efforts…” (Juul 9). Dear Esther’s deliberately vague narrative storyline does just that, without the distractions of the aforementioned traditional gameplay elements.

The one downside of analyzing Dear Esther as a narrative gaming experience is that, as mentioned earlier, it is highly debatable whether this interactive narrative experience is even a “video game.” The next two games in this paper will delve more into how narration can interlock with specific gameplay elements and in what ways the interactive narrative experience can be applied to more than just experimental games like Dear Esther.

To the Moon and Emotion-Driven Narration

To the Moon is a top-down 16-bit-styled adventure title created by Freebird Games. It follows the story of Dr. Rosalene and Dr. Watts, who work for an organization that constructs memories for people who are about to die. In this case, Dr. Rosalene and Dr. Watts are trying to construct and fulfill the lifelong wish of old Johnny Wiles, who for his whole life dreamt of going to the moon. However, the two scientists soon realize that they must fight Johnny’s past in order to make his dream come true.

Experiencing and deliberately altering the past of this fictional character through gameplay is the reason why popular YouTube star PewDiePie told his millions of subscribers “you can’t play this game without crying” (Kjellberg). When you first boot up the game, little is known about Johnny’s past, but as the player ventures deeper into the memories of Johnny’s mind, it becomes apparent that he lived quite a distressing life. It seems that the further the two doctors go into Johnny’s mind, the more mysterious his past seems to become, especially when it comes to Johnny’s deceased wife, River, who seems to be the source of Johnny’s discomfort. This instance is an example of “motivation technique,” the idea that creating intriguing mysteries will motivate the player to progress through the story in order to solve the mystery (Freeman 5). What makes motivation techniques unique in video games is that the mystery is oftentimes a part of the player’s goal, a conflict that the player must solve in order to complete the game.

However, this seems to be a general theory that encompasses most contemporary video games. Why then, does To the Moon evoke so much emotion from the player when other games do not? Perhaps it is because the conflict ties to a living person, especially one who is the love interest of one of the game’s more-significant characters. The ambiguity of information regarding River’s character is perplexing, and the abstract clues that the player discovers throughout the game add a sense of emotional depth. This is accomplished using in-game symbols, which Freeman (2004) describes as one of the pathways to “emotioneering,” or “the expansive body of techniques for evoking emotional breadth and depth in games.” (Freeman 4). The idea is that symbolic objects can play a role in eliciting emotional responses not only in storytelling but also in gameplay. To the Moon accomplishes this by forcing the player to find substantive symbols in Johnny’s past to further progress into his memories, among them a stuffed platypus he gives to River when they were young. Thus, unlike Dear Esther, To the Moon does not simply tell a story through player exploration, but also takes advantage of gameplay elements such as the collection of items to expand the narrative experience and add emotional depth for the player.

Deane et al. (2013) lists five basic methods of emotional engagement in their paper: characters, relationships/dialogue, plot/narrative, atmosphere and environment, and game moments/challenges. Dear Esther only covers one of these elements, that is, the latter half of plot/narrative. To the Moon goes deeper by stimulating emotional investment in its characters in addition to a well-developed plot. However, what of the three remaining elements that have yet to be accounted for? While Dear Esther and To The Moon appeal to only certain elements of emotional engagement, one other game, The Walking Dead, manages to utilize every aspect of Dean’s list to create a fully-realized emotional experience.

The Walking Dead and Player Choice

The Walking Dead is an episodic adventure video game developed by Telltale Games. It is akin to the point-and-click adventure games of the early 1990’s, but with the addition of modern video game elements like cinematic cut scenes and full voice acting. The player takes control of Lee Everett, a convicted murderer who gets involved in a car accident on his way to prison. When he wakes up, he realizes that he is in the middle of the zombie apocalypse, and thus needs to figure out a way to survive for the days to come.

The most prominent feature of The Walking Dead is the way it incorporates player choice into the gameplay. Much of the game involves talking to the other characters and choosing how to continue Lee’s conversation with them. Each choice will result in a different outcome that will affect how the other characters will respond to you and ultimately alter the game’s main plotline. This is a unique aspect in video games called “multiform stories” and allows the player to play a game multiple times and experience it differently each time given that he or she makes different decisions in each playthrough (Ostenson 77). Developers utilize “agency techniques” – elements that give the user control over what happens next – to achieve this and make the player feel like their decisions have significant impact to the game’s story (Freeman 10).

The Walking Dead succeeds in giving players agency partly by making the players care about the characters. While the goal of the game is to keep Lee alive until the final episode, he can only do so if he cooperates with other characters (or, in some cases, eliminate those that are threatening). This becomes a challenge when the game throws situations at you that cannot be easily resolved, especially when you have to decide the life or death of one character over another. For example, should you save the 10-year-old child of a man you just met, or should you save the 20-year-old whose family is currently giving you shelter? Freeman calls these events “emotionally complex situations,” in which the player must decide between two outcomes, neither of which seem favorable over the other (Freeman 5).

While The Walking Dead utilizes its gameplay mechanics in many different ways to tell its story, there is one other aspect that seems to evoke the most emotion from its players: Lee’s relationship with Clementine, a young girl who lost her parents in the apocalypse. Lee meets Clementine early in the game, and upon hearing her story decides to adopt her for the time being. Because the game focuses on the player giving commands to Lee, it is almost as if the player is Lee; thus, when Lee begins to take care of Clementine, it feels like it is the player who is actually taking care of the little girl. This “psychological proximity” between the player and the main character can only be accomplished in a game like The Walking Dead, where the player is given a perceived freedom of choice in relation to the environment and other characters (Dickey 76). This action of giving the player the responsibility to take care of another, lesser character is also known as “role-induction technique” and gives off the impression that the protagonist is an all-around hero, even if he is in fact a murderer, as in the case of The Walking Dead (Freeman 5).

Going back to Deane’s five methods of emotional engagement, it is easy to see how The Walking Dead meets the criteria for every element on the list; the game focuses on the relationship between the characters Lee and Clementine among others, presents relationships and dialogue as a major gameplay mechanic that involves player choice, introduces a multiform plotline influenced by these choices, sets the player in an unstable post-apocalyptic environment that entails difficult decisions, and provides challenges required to make these decisions.

Final Remarks

Unlike traditional storytelling media, video games allow the player to experience the story rather than merely consuming it.

Video games are a rapidly evolving medium that in the past half a decade has changed the way people experience storytelling. Unlike traditional storytelling media, video games allow the player to experience the story rather than merely consuming it. Dear Esther's story is cryptic and purposefully vague, forcing the player to think about the subject matter at hand instead of focusing on traditional gameplay mechanics. To the Moon uses motivation techniques and symbolic imagery to add depth to its characters and the overall emotional depth of the narrative. The Walking Dead's multiform story gives players the agency to decide the game’s plot direction, which demands that the player make decisions in emotionally complex situations between themselves and other characters. Games like these show how far video games have come in terms of a narrative experience and ensures their place as an effective storytelling medium for years to come. As technology continues to improve at an unprecedented rate, so too will the quality of these narrative-focused video games and the amount of emotional engagement found within these interactive experiences.

Works Cited

Briscoe, Robert. "About." Dear Esther. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2013.

Deane, Josh, et al. "Emotional Engagement In Video Games." (2013).

Dickey, Michele D. "Engaging by design: How engagement strategies in popular computer and video games can inform instructional design."Educational Technology Research and Development 53.2 (2005): 67-83.

Freeman, David. "Creating emotion in games: The craft and art of emotioneering™." Computers in Entertainment (CIE) 2.3 (2004): 15-15.

Kjellberg, Felix. "To The Moon - LET THE TEARS BEGIN!.. - To The Moon - Part 1 - Let's Play Walkthrough Playthrough" Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 15 Aug. 2012. Web. 10 Nov. 2013.

Kuchera, Ben. "Dear Esther Is a Game, but You Have to Bend to Its Will to Enjoy the Experience." The PA Report. Penny Arcade, 19 Feb. 2012. Web. 10 Nov. 2013.

Juul, Jesper. "Games telling stories? A brief note on games and narratives." Game studies 1.1 (2001): 40-62.

Ostenson, Jonathan. "Exploring the Boundaries of Narrative: Video Games in the English Classroom." (2013).

![Amazing Spider-Man Finale Features New [SPOILER] Costume](../../../../../../assets1.ignimgs.com/2018/06/01/untitled-br-1527892808294_small.jpg)